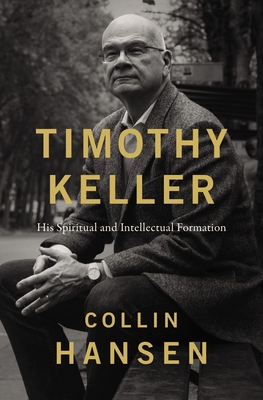

“Of making many books there is no end” – Ecclesiastes 12:12

Last week I traveled to Toronto for the annual convention of my denomination, the Fellowship of Evangelical Baptist Churches in Canada – or The Fellowship for short. It was there that every delegate from around the country received a free copy of the book I’ve been working on for over a year, a revised and expanded second edition of A Glorious Fellowship of Churches, which tells the history of our little denomination. This was a collaborative effort with the esteemed historian Dr. Michael Haykin, our second such partnership. In this post I describe a bit of what that process was like and then reflect on what I took away from the experience.

As I’ve mentioned before, this was a special project for me to work on because the first edition, published in 2003, was worked on by my mother, Ginette Cotnoir, who served as the editor of the Fellowship’s magazine: then called The Evangelical Baptist and subsequently rebranded to Thrive. She worked with longtime missionary pastor Ernie Keefe on the chapter dealing with Quebec. For the second edition, updating that chapter to cover the time period from its publication in 2003 to current day (2023) was my main writing assignment. This meant interviews with several key leaders and research through annual reports, books, etc. The chapter was already quite long, so there was quite a bit of tightening up to do to make room for the new content. Then the whole thing needed a careful edit so that the narrative voice of the chapter was consistent and enjoyable to read. The main challenge there was to create a bit of distance between the narrator and the narrative. Mr. Keefe – a good and godly man – was a bit wordy and wrote in a style more reminiscent of a missionary update than a history book.

Beyond the writing, the project required a lot of communication, coordination, and editing. Each chapter needed to be expanded to cover the last twenty years, but aside from one chapter, none of the original authors were available to do the work. So this meant finding someone willing to take on the unenviable task of researching and writing a few thousand words of recent history and trying to meld it smoothly into an existing chapter written by someone else completely – with nothing but a “Thank You” and a free copy of the book to show for it. No wonder we had such a hard time finding willing souls for some of the chapters. But in the end we got contributors lined up and I gave them clear instructions as well as a deadline. All of this started well over a year ago, in August of 2022.

Once I received all the chapter updates, I simply blocked off chunks of time in the evenings and went through all the new text with a fine-toothed comb, and then the entire chapter as a whole. There was also one entirely new chapter, written by Steven Jones, the president of the Fellowship since 2011, which dealt with national ministries and how the head office has morphed and changed over the years. It was a needed addition as the first edition did not really deal with the big picture national issues at all.

The last few weeks were a blur of proofreading, sourcing pictures, and putting the finishing touches on the book. Then off to the printers it went, with no small worry in my mind that they might not actually be ready in time for the convention. I could just imagine showing up there and having to tell everyone it would be a week late. But then an email came in on the Friday, just three days before the opening day. The books had arrived! I slept well that night.

My first glimpse of the physical copies happened as I approached the registration tables to get my lanyard and nametag. Then my name wasn’t in their system, and I had to go to another table. After a few minutes, they printed one up for me, and handed me a tote bag with pamphlets and brochures for the conference, but no book. I pointed a bit sheepishly at the pile of books and asked if I could perhaps have a copy. “Sorry, the book is only for those registered as delegates.”

I was not a delegate that year, so I wasn’t sure what to say. I knew I’d be getting a free copy somehow, but I didn’t really want to plead my case at the busy registration table, so I was about to smile and walk away when my friend spoke up and told them that I had worked on it and pointed out my name on the front cover. How nice to have an advocate. So I got a copy of the book and held it in my hands, a very satisfying moment. It looks and feels great. It’s a bit thicker than we expected, but the font is quite large, with generous margins, and lots of colour pictures throughout. So while it feels a bit thick in the hand, it doesn’t feel dense, and therefore not overly intimidating.

So what did I take away from all this? Let me single out four things:

- The Importance of Roots

We all love a good tree analogy, do we not? Trees need strong roots. They cannot grow tall or broad without them. Christians and churches and denominations are similar. If there is a consistent weakness in evangelical Baptist groups, it is historical rootlessness. Many of us simply do not know where we came from. This was certainly the case for me growing up. And although this was probably exacerbated by the unusual context of my upbringing, being a part of a church filled with first-generation Christians coming out of a dead French-Canadian Catholicism, it is still a defining feature of evangelicals more broadly. This explains to some part the exodus from evangelicalism to Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and Anglicanism – three branches of Christianity which emphasize their historical continuity far more than we do.

This was illustrated powerfully by a comment made by Dr. Haykin during a workshop session he gave at the conference. He described how, upon coming to Christ as a young man through the ministry of Stanley Park Baptist Church in Hamilton, he asked his leaders: “Where do Baptists come from?!” But he received no real compelling answer, aside from a suggestion that maybe the folks at Wycliffe College could help him, and that set him on the path to becoming one of the foremost Baptist church historians in the world.

This rootlessness has driven a lot of my own reading and intellectual curiosity over the last two decades. I’ve become convinced that within historic Protestantism, which is in continuity with the best of the ancient and medieval church, we have abundant resources for growing deep, healthy roots. So the problem is not a lack of nutrients but the prevailing alienation from those nutrients and, even worse, an attitude that assumes that the modern church has no need for all that old stuff.

Working on this book reminded me in a fresh way how stabilizing and encouraging it can be to discover one’s roots. The history of the churches that make up the Fellowship in some cases go back to the 18th and 19th centuries. The list of faithful men and women who built and sustained all those churches is long, and we shuffle onto the stage in their wake, holding their props, and seeking to carry on the faithful work they left us. Each new generation receives this legacy from the one before. And that, if it sinks down deep, helps us chart a path that is straight and true.

2. The Nearly-Forgotten Faithful

There are a few names in church history that everybody knows: Augustine, Aquinas, Luther, Whitefield, Spurgeon, Billy Graham. We continue to read and write books about them because of their compelling personalities and the momentous nature of their ministries. But for each of us, there is another, closer set of ancestors – locally, regionally, and nationally – who more directly shaped the church family in which we find ourselves. It is good and right for us to make the effort to remember these men and women. Unlike with Luther and Augustine, if we don’t remember them, no one will. As the spiritual descendants of these saints, it is our responsibility to remember them, to rehearse the works God did through them, and to honour their memory. This seems to me to flow naturally out of the repeated chorus we find throughout the Old Testament to remember the works of God in previous generations.

I’m so glad to have been a part of writing a history of The Fellowship, for I think it helps preserve the health and future of that movement of churches. It helps us remember who we are, and what we’re a part of. The narrower scope means that the book won’t sell thousands of copies, that’s true, but I think it has the potential to have a deeper impact on those who are part of The Fellowship as a result of that narrower focus.

3. The Forgotten Faithful

But here is the reality that we all must embrace: the vast majority of God’s people are, in a human sense, utterly forgotten within a short period of time after their death. This was a curious effect of my research and reading. As I came across name after name I had never heard of before, it impressed upon my mind the reality that there was simply no end to the names or the stories. I could never hear all of them, know all of them, or capture them rightly in words. And yet each of them played their parts through prayer and service and teaching and outreach and building and sowing and reaping, no less than anyone else.

Friends, this is going to be case with you and me, almost certainly. Few will make it into whatever history books are written, and that’s okay. As I heard it put many years ago, there will be only one name lifted high in the new heavens and new earth, and it won’t be yours or mine. The sooner we get on board with that, the better.

4. Don’t Live for the Next Achievement

If you had told me three years ago that I would have gotten multiple articles published and edited a couple of books with real publishers I would hardly have believed it was possible. I had wanted to explore the writing and publishing world for years, but never really saw how that could happen. So I find myself both deeply grateful for these opportunities and also sobered by the fact that the buzz I get from every new venture doesn’t last long.

Thankfully, I am not looking to my writing and editing to give my life meaning; it already has that. I get a joy from using my gifts and all the usual human sensations that come with trying your hand at something new and getting positive feedback. And on the flip side, when that new article is submitted to a new outlet or the new book manuscript sits almost finished but unsent to the publisher, there’s a typical insecurity wondering if it’s any good at all. This is par for the course for writers (and a recurring joke – Anne Lamott’s writing is pretty hilarious on this point). I hate to think how neurotic I would be if I was looking to these kinds of achievements to give my life meaning or secure my identity.

Let me close with an application of this truth. It may not be writing in your life, but maybe there’s some next thing that you’re aiming for and investing just a little too much security and joy into. Maybe it’s a new ministry position, a new relationship, a new church, a work promotion, or even a new car. Well, get ready to be disappointed. None of these things can fill our cup to overflowing.

But there is something which can: a living union with the risen Christ through the Holy Spirit; knowing and being known by God our exceeding joy.

(Update: The book is available to purchase via this link: https://www.fellowship.ca/GloriousFellowship70thAnniversaryEdition)