Somehow I have never read ‘Miracles’ until now. I listened to it, narrated by a very good narrator, and really enjoyed it. Lewis’ prose is so striking and memorable – but why? It is a strange mixture of dense rational arguments, conversational tone, and colourful illustrations. There is a strong undercurrent of wit and humour spread throughout the whole thing. This kind of writing is a pleasure to take in, even when you don’t agree with it. Chesterton is the same way, though perhaps more effortlessly funny.

Lewis here is writing in the mid-20th century in an intellectual climate that is modernist and naturalistic. He is concerned about making a robust defense of miracles, but really miracles is just an entryway into a far more expansive discussion that centrally takes aim at the hubris of modernist metaphysics (naturalism) and, having disarmed it, makes a strong case for the reasonableness of the Christian faith which includes the central Christian miracles of the incarnation and resurrection.

It’s worth noting that he presents the incarnation as the central Christian miracle in a way that evangelical apologists have typically presented the resurrection. Lewis is in line with the early church here more than contemporary evangelical apologists, I believe, and my hunch is that this difference is not disconnected from the relative weakness of evangelical anthropology – our understanding of the human person and human nature. Which is not to take anything away from the importance of the bodily resurrection, of course.

This book is also a prime example of what makes Lewis so rewarding to read: his writing has aged so well. In fact, his analysis and prognosis of Western culture was so perceptive and ahead of its time that some of the books that were largely ignored in his lifetime have surged in popularity only in the last couple of decades, such as The Abolition of Man and That Hideous Strength. To a lesser degree, this is true of Miracles as well.

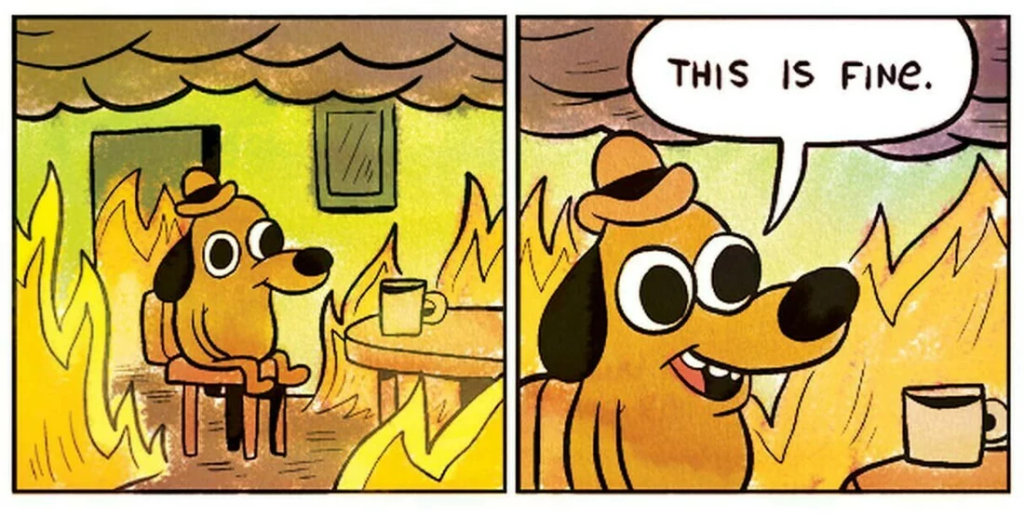

One of the most perceptive writers of recent years has been Dr. Iain McGilchrist, a psychologist and cultural critic who specializes in the way the brain hemispheres affect our modes of thinking. His work is fairly popular now, as one can see by the flowering of discussion about the left vs right brain kinds of thinking. He argues that the left hemisphere, which specializes in a narrow focus of attention for manipulating and controlling elements of our environment, has become dominant in the modern era. But the left hemisphere was always meant to be subservient to the broader-scoped, more intuitive and open right hemisphere. He argues that many of our modern psychological and social ills are related to this left-brain dominated mode of thinking.

Here again Lewis seems to have anticipated this state of affairs, this modern crisis. He was himself a man of unusual gifts in this exact regard, as John Piper helpfully explored in his conference and subsequent collaborative book called ‘The Romantic Rationalist’. In short, Lewis’s mind was a remarkable marriage between the left-brained hardnosed rationalism that he imbibed from his beloved tutor William Kirkpatrick, ‘the Great Knock’, and the right-brained imaginative intuition and romanticism. How many other authors have managed to write works of fiction (imaginative) and non-fiction (rational) that have endured so well?

These two passages here illustrate how prescient Lewis was in his diagnosis of the modern mental malady. The first passage traces the process of increasingly “truncated thought.”

“There is thus a tendency in the study of Nature to make us forget the most obvious fact of all. And since the Sixteenth Century, when Science was born, the minds of men have been increasingly turned outward, to know Nature and to master her. They have been increasingly engaged on those specialised inquiries for which truncated thought is the correct method. It is therefore not in the least astonishing that they should have forgotten the evidence for the Supernatural. The deeply ingrained habit of truncated thought—what we call the ‘scientific’ habit of mind—was indeed certain to lead to Naturalism, unless this tendency were continually corrected from some other source. But no other source was at hand, for during the same period men of science were coming to be metaphysically and theologically uneducated.” (Chapter 6).

In this second passage, Lewis argues that Christianity is uniquely equipped to bridge the “unbridgeable chasm” that has grown between the two different ways of thinking.

“There is thus in the history of human thought, as elsewhere, a pattern of death and re-birth. The old, richly imaginative thought which still survives in Plato has to submit to the deathlike, but indispensable, process of logical analysis: nature and spirit, matter and mind, fact and myth, the literal and the metaphorical, have to be more and more sharply separated, till at last a purely mathematical universe and a purely subjective mind confront one another across an unbridgeable chasm. But from this descent also, if thought itself is to survive, there must be re-ascent and the Christian conception provides for it. Those who attain the glorious resurrection will see the dry bones clothed again with flesh, the fact and the myth remarried, the literal and the metaphorical rushing together.” (Chapter 16).

As you can see, the book is brilliant and worthy of close scrutiny.

Another element that stood out to me was the way Lewis based his central argument against naturalism in the mystery of human consciousness and the mystery of human thought. I don’t know if consciousness studies were in vogue in the mid-20th century, but I know they have exploded in popularity in recent years. And somehow everything Lewis said about cognition and consciousness aligned with what I understand (as a layman) to be the best ‘theory of mind’ out there.

For a book that is nearly 80 years old, that is remarkable.