“Marriage is a duel to the death which no man of honour should decline.” – G. K. Chesterton

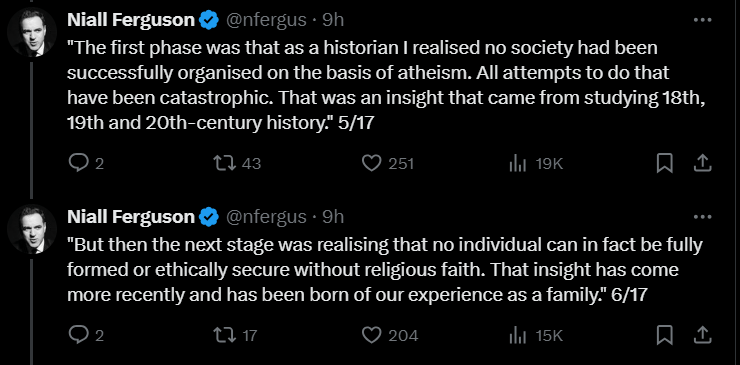

There is something rotten in the state of the relation between the sexes. The statistics are consistently bleak. Young people are not getting married, or they are getting married much later; birth rates in the developed world are plummeting; a new political divergence between the sexes is emerging, with women predominantly leaning progressive and men increasingly drawn to the right; dating moved from the analog world to the internet, from the internet to dating apps, and now the conclusion seems to be that dating apps have made romance worst, not better.

Even the romantic comedy movie genre seems like an artifact from a previous, more innocent era. It feels like, as a society, we have quite forgotten how to fall in love. We have lost romance, and I almost feel nostalgic for the problems we had with the excess of romance. What killed romance? I don’t pretend to know the full answer to such a question, but clearly pornography has played a leading role. With young men (and women) typically being exposed to violent pornography in early adolescence, what chance does friendship really have to flower into attraction or romance?

Pornography takes the sacred consummation of covenantal love, the apogee of romance between two human persons, and desecrates it, reducing it to mere animal urges. By this defiling of the marriage bed the entire chain of romance is broken. If love is meant to grow organically and naturally between a young man and a young maiden, it’s difficult to come up with anything that could so deeply derail that enchanted procession as the mixture of dating apps and pornography that characterizes the modern mating market.

But there is good news, because I am convinced the church of Christ has an important role to play in preserving and modeling a healthy culture of romance and marriage for a watching world that has so completely lost its way. The culture is disillusioned and exhausted, tired of the cynicism and the failed promises of ever-more-freedom, one-more-hookup, the-transgression-of-one-more-sexual-taboo as the answer to all our problems. Into this dysfunction, the church has an opportunity to show a better way: marriages that reveal a complementarity in harmony with the created order and that manifest genuine friendship, romance, and selfless love.

It’s in Genesis that we find the original blueprint for the relations between the sexes as well as the defining characteristics of how sin has marred this blueprint ever since the fall. When I was a campus student leader at Bible College, I started to notice something troubling percolating among the student body. What I noticed was a spirit of division growing up between the young men and young women, fueled by a narrative of grievances between the two groups. It resembled the kinds of attitudes that are sadly all too common in the public square whenever discussion turns to the relations between the sexes. I also started noticing that the harmony that had existed between the men and women began to be frayed and strained as both sides were pressured to find solidarity primarily within their own gender grouping.

As a student leader this was very concerning to me because one of the most wholesome aspects to on-campus student life had been precisely the absence of these divisions. Indeed there was a healthy amount of brotherly and sisterly affection which was openly expressed between the hundred or so 18-25 year-olds who made up our little community.

It was to Genesis that we turned to find language to describe the problem we were facing. An honest reading of Genesis 3 made the nature of the perennial problem clear: men tended to be too passive or to dominate selfishly and women tended to usurp or undermine the men. Each side can always feel smug and satisfied by focusing on the sins and failures of the other group. And as long as this is what we do, we can be sure we’ll never get anywhere good. Part of the answer was just laying out this deep-rooted dynamic for all to see. These conversations were illuminating and convicting, and many humbled themselves in repentance when they identified how they had been contributing to the division.

The next step was giving them a vision of an alternative to the mutual suspicion and division that we see so much of. The New Testament provides the blueprint: that of the redeemed household, with brothers, sisters, aunts, and uncles. In a healthy family, siblings genuinely want the best for one another. I do think there are natural limits on what kinds of personal friendships can exist between men and women before the inevitable complications arise, but that’s a topic for another time. For now, we can simply assert that the brotherly love Christians are to have for one another includes everyone, male and female.

That addresses, if partially, the division and hostility between the sexes, but what about romance?

Here we find more to work with in the Old Testament than in the New. We have a number of narratives that seem to be more than merely descriptive, even if they are tainted by sin: Jacob and Leah, Ruth and Boaz, but especially the love poetry par excellence, the Song of Songs. Add to that this enigmatic Proverb:

“There are three things that are too amazing for me,

four that I do not understand:

the way of an eagle in the sky,

the way of a snake on a rock,

the way of a ship on the high seas,

and the way of a man with a young woman” (Prov 30:18-19).

Pondering these Scriptural depictions of romance will go a long way to correcting some of the worst confusions and distortions of our day. One of the things that becomes clear from these passages is that the experience of falling in love is a great good gift. Yes, it needs to be informed by wisdom and protected from the predations of sin, but it is good.

The relations between the sexes are fraught. In marriage, we find the reconciliation of the sexes that serves as a blueprint for peace. A happily married person, in view of their love and partnership with someone of the opposite sex, will necessarily be far slower to participate in broadsides against the other sex.

In Christian marriage, we find not only that, but a living picture of the gospel itself. Indeed, the Bible is clear that marriage, far from being an arbitrary arrangement that allows for the continuation of the species, is of cosmic significance, for it was designed from the very beginning to reveal something glorious about God: ”This is a profound mystery—but I am talking about Christ and the church” (Eph. 5:32).

In our day of relational carnage, a thriving marriage is a beacon of light, a promise that there is a better way than what the world offers. May the church be a place that welcomes the many wounded refugees from the gender war, a place where such people can learn God’s good design for men and women and even, perhaps, a place where they can do what men and women have always done: fall in love and get hitched.

(Happy 16th anniversary to my lovely wife, Kaitlyn, God’s great good gift to me).